Yilpinji: Love, Magic & Ceremony: Group Show

This exhibition explores the visual tradition relating to yilpinji, the love magic practiced by the Warlpiri and Kukatja people of the central and western deserts of Australia.

While a rich tradition of love songs, poetry, drama and other literature exists in the English language, this exhibition demonstrates clearly that the theme of love in art is not the exclusive preserve of Western art. It is less well known – or perhaps not known at all in some quarters – that here is, in fact, an equally rich and even longer tradition of Aboriginal Australian love poetry, song and visual art pertaining to love.

In Western art, love is a pervasive theme in cinema, as exemplified by the maudlin, mawkish quote from Love Story, and the theme and subject matter of love are threads that are woven through art history, appearing in all art forms. The theme of love is to be found in high art and popular culture alike. Examples that come to mind are the troubadour tradition, the love sonnets of Shakespeare, the work of William Blake, Jane Austen, Elizabeth Browning and more recently still, Patrick White and Adrienne Rich, to name but a few. D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterly’s Lover, Radclyffe Brown’s Well of Lonliness, Nabokov’s Lolita and Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint are explorations of less socially acceptable (at least at the time they were written) or perverse expressions of sexual love. These books encountered censorship following a storm of protest at the time they were first published.

Love – either socially sanctioned or in some way transgressing normative social or ethical boundaries and values – appears repeatedly as the focus of subject matter of a great deal of both Western and Aboriginal visual art. In European visual arts and literature, both oral and written, the list of artworks making reference to love would be as extensive as the theme’s literary manifestations. Anglo-European visual arts frequently express sexual love in all of its iterations, including its sometimes perverse and socially transgressive expressions. Among the multitude of possible examples are the many artistic representations of the ‘interspecies love’ between Leda and the Swan (for example, Leonardo da Vinci’s work of 1507; as well as works by Michelangelo, Raphael and Corregio, inter alia); David’s painting The Love of Paris and Helen (1788); and Gerard’s famous Amor and Psyche, also known as Psyche Receiving the First Kiss of Love. The latter two works are both housed in the Louvre. In more recent times, Picasso’s many depictions of his wives and mistresses; Max Ernst’s 1923 work Long Live Love or: Pays Charmant, in the Saint Louis Art Museum, U.S.; and even more recently still, Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographic oeuvre spring to mind. Of course there are many more examples from both literature and visual dating back to the Egyptians, the Ancient Greeks (for example Sappho’s love) and the Romans and the Italians (most famously, some of Dante’s works).

Contrastingly, for the Warlpiri and the Kukatja people of Australia’s tanami desert region, the primary seat of the emotions is not the heart, but the stomach. Happiness, sadness, rage, anger, desire, concern, anxiety, depression, feelings of protectiveness and responsibility towards others, indeed all the intuitive faculties are thought to be located in one’s miyalu or stomach. The late Warlpiri linguist and teacher Paddy Patrick Jangala, in his quote at the beginning of the essay, provides evidence of a people in whose lives romance and sexual love plan an extremely significant part.

Yilpinji is when men sing with other men to get women to fall in love with them. The women fall in love with them* as a result of being seduced by the yilpinji songs – in this way each man attracts a woman….A man sings love songs to attract the object of his affections, his desired lover, to him and in the same way a woman may also sing yilpinji [in an all woman group] to charm a man who is her beloved, and the object of her sexual desire** with powerful love songs…. ‘Waninjawarnu’ [‘from the throat’] is when a man and a woman fall in love with each other in their inner feelings, in their heart and soul [literally throat and stomach].

*literally, sing the women to their, i.e. the men’s throats

**literally brings the man ‘to her throat’

In Australian Indigenous art, there are many interesting contrasts with Anglo-European traditions. As evidenced from the quote above, falling in love Warlpiri - or Kukatja-style is conceptualized very differently, in terms of the preferred metaphors used to describe the experience. For Anglo-Europeans, the heart is considered to be the seat of the emotions, of feelings, intuition, and love, whether that love is caritas or eros.

While in English there are expressions like ‘broken-hearted’, ‘heart breaking’, ‘heart-rending’, ‘heartache’, ‘open-hearted’, or ‘heart-throb’ used to describe a sexually attractive person, there exists an equally rich vocabulary pertaining to the emotions in the Warlpiri language and the Kukatja language that is centered on the stomach as the seat of human emotions. For example, ‘miyalu-kari’ (literally, other-stomached) describes a person in a state of being low in spirits, that is, a person who is depressed, or down-at-heart, as the English idiom goes; miyalu raa-pinyi (literally, to open up one’s stomach) means to make someone happy, as, for example, in the sentence: ‘Ngulaji miyaluju raa-pungu, wardinyarramanu-juku’ (He opened my stomach, he made me happy’).

While the stomach is the principal seat of the emotions for the Warlpiri and the Kukatja, the throat (‘waninja’) is the primary location of sexual love and attraction. Amorous feelings, sexual yearning and attraction are all located, deeply felt and experienced in the throat (as opposed to the heart). Falling in love is described as ‘waninja-nyinami’ (emotion that is literally ‘throat-sitting’ or ‘throat-located’). When Warlpiri and Kukatja people fall in love, it gets them in the throat, not in the heart. For this reason special significance relates to necklaces and other body adornments worn about the neck, close to one’s throat, and they are often used in ceremonies pertaining to love. Often these are woven out of hairstring and used in yilpinji ceremonies.

It is clear from the above that while the actual experience of sexual desire and falling in love may not differ greatly from culture to culture, the metaphors used to talk ‘the language of love’ may be very different inter-culturally. In part the body of works in this exhibition has an educational focus insofar as it demonstrates an aspect of Indigenous life that has been so little understood or discussed in the past. Misguidedly, some non-Indigenous academics have claimed that Indigenous languages lack a vocabulary to describe the emotions. In my view such attitudes are founded on ignorance which one hopes will at least partially be contested and challenged by this exhibition.

These limited edition prints by Old Masters from the predominantly Kukatja settlement of Wirrimanu (Balgo Hills) in Western Australia as well as from Yuendumu and Lajamanu, Warlpiri settlements in the Northern Territory, have come about as the result of a unique cross-cultural collaboration. It has involved Aboriginal artists, remote art center staff and community organizations, a fine art print publishing house, a number of anthropologists who have specialized knowledge of these cultural groups, and two highly respected non-Indigenous printmakers.

The Kukatja and the Warlpiri people have powerful traditions of love magic rituals and ceremonies, involving the singing of secret love songs as well as other forms of artistic expression. Sometimes this involves the painting of special designs onto their bodies or the production of ‘love objects’ to enact these ceremonies. Called ‘Yilpinji’ in the Warlpiri language, these ceremonies are enacted separately by men and women as a means of attracting the object of their sometimes adulterous or otherwise forbidden desire. In addition, many Dreaming narratives and associated ceremonies belonging to the Kukatja and Warlpiri peoples make powerful statements about the consequences of illicit, illegal love – love that is, that offends the strict riles of their kinship structures. For example, amongst Warlpiri and Kukatja people the ‘love that dare not speak its name’ may well be the love (or lust) of a son-in-law for his mother-in-law, or vice versa.

Paintings of Yilpinji not only relate to moral and ethical behavior and the transgressions that sometimes occur but, like other Dreaming narratives, they are attached to specific tracts of land. The often lengthy narratives associated with the Yilpinji paintings provide guidance about how (ideally) people should interrelate with one’s fellow human beings as well as providing templates for their interactions with other species and with the natural world. Dreaming narratives relating to Love Magic ceremonies and themes have a range of manifestations and iterations, and can be expressed through a variety of art forms.

Dreaming narratives are deemed to be owned (a form of orally transmitted copyright) by certain individuals and groups (communal ownership) within indigenous kinship systems. Usually only certain parts of Dreaming narratives are made publicly available to outsiders or children. The paintings act as mnemonic devices for the longer narratives associated with them. Dreaming narratives closely relate to specific tracts of land and environmental features. At the same time they deal with the ‘big’ or important philosophical, spiritual, moral and ethical subjects. These include life, death, betrayal, dishonesty in relationships, love, hate, lust, incest and other extreme emotions and practices. Sexuality, family relationships, relationships between humans and other species are included as well as relationships between human beings and the environments, youth, aging, physical and psychological survival, birth, death, how to raise children, compassion, generosity, meanness and the like. Many of these Dreaming narratives and their accompanying visual manifestations have a Yilpinji (poorly translated as ‘love magic’) component, providing advice on how not to act, as well as indicating desirable behavior.

In addition, Love Magic charms, spells and songs relate to the many different Dreaming narratives on which the prints in this exhibition are founded. The works here include stories about objects which ‘hold’ love magic, relay information about powerful love ‘singers’ (some good, some evil), as well as relating tales about long term faithfulness in love relationships and the virtures of nurturing and respecting the object of one’s love and desire. This includes the terrible consequences of uncontrolled sexual passion. The paintings, prints and other visual imagery relating to this subject matter can be understood as concentrated, abbreviated versions of these much longer oral narratives.

All of the works in this exhibition in some way relate to the theme of love, or love magic (yilpinji) in the Warlpiri and Kukatja contexts and reveal a rich repository of cultural knowledge about this subject. Equally, there are many long, complex, different and fascinating stories relating to all of the art works exhibited here. This is a significant exhibition because it introduces the non-Indigenous world to a critically important but previously little-known aspect of Indigenous social life.

The folio of prints by these accomplished and knowledgeable artists, men and women of ‘high degree’, explore such themes through the powerful medium of the visual arts.

Dr. Christine Nicholls

Senior Lecturer, Australian Studies

School of Humanities, Flinders University

-

Paddy Japaljarri Sims, Yanjirlpiri – Star, n.d.

Paddy Japaljarri Sims, Yanjirlpiri – Star, n.d. -

Rosie Tasman Napurrula, Grass Seed Dreaming, 2003

Rosie Tasman Napurrula, Grass Seed Dreaming, 2003 -

Judy Napangardi Watson, Love Story

Judy Napangardi Watson, Love Story -

Paddy Stewart Japaljarri, Ngarlu Jukurrpa – Love Story Dreaming , n.d.

Paddy Stewart Japaljarri, Ngarlu Jukurrpa – Love Story Dreaming , n.d. -

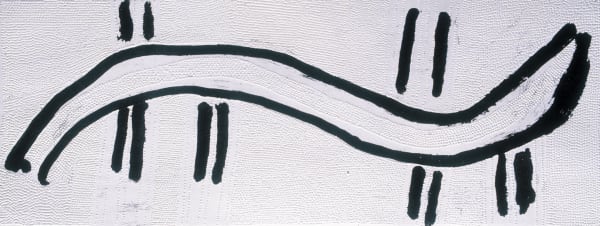

Teddy Morrison Jupurrurla, Wamparna – Bush Wallaby , 2003

Teddy Morrison Jupurrurla, Wamparna – Bush Wallaby , 2003 -

Teddy Morrison Jupurrurla, Kulukuku-Wild Bush Dove, 2003

Teddy Morrison Jupurrurla, Kulukuku-Wild Bush Dove, 2003 -

Ronnie Lawson Tjakamarra, Janmarda - Bush Onion, 1997

Ronnie Lawson Tjakamarra, Janmarda - Bush Onion, 1997 -

Liddy Nelson Nakamarra, Yumurrpa – Big Bush Potato , 2002

Liddy Nelson Nakamarra, Yumurrpa – Big Bush Potato , 2002 -

Liddy Nelson Nakamarra, Wapurtarli – Little Bush Potato, 2002

Liddy Nelson Nakamarra, Wapurtarli – Little Bush Potato, 2002 -

Tjumpo Tjapanangka, Tjumpo Tjapanangka

Tjumpo Tjapanangka, Tjumpo Tjapanangka -

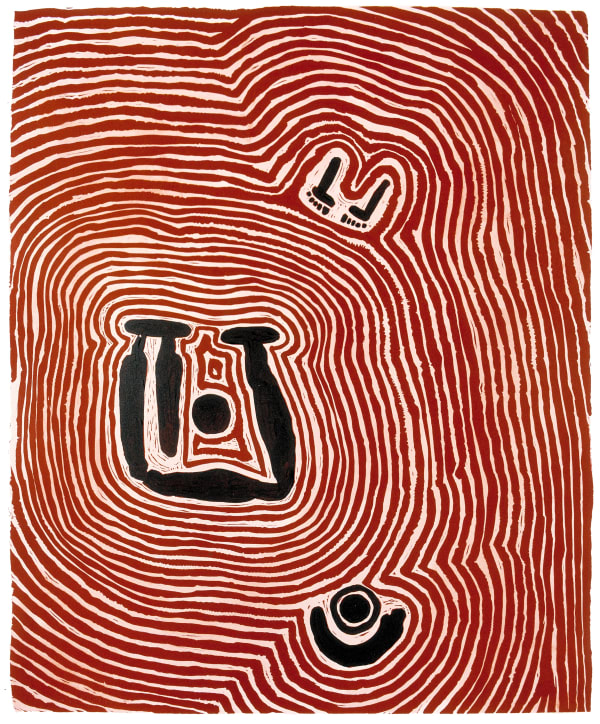

Tjumpo Tjapanangka, Love Magic Place

Tjumpo Tjapanangka, Love Magic Place -

Molly Tasman Napurrurla, Wild Bush Plum , n.d.

Molly Tasman Napurrurla, Wild Bush Plum , n.d. -

Lucy Napanangka Yukenbarri, Punyarnita I

Lucy Napanangka Yukenbarri, Punyarnita I -

Lucy Napanangka Yukenbarri, Punyarnita II

Lucy Napanangka Yukenbarri, Punyarnita II -

Abje Jangala, Katinpatimpa

Abje Jangala, Katinpatimpa -

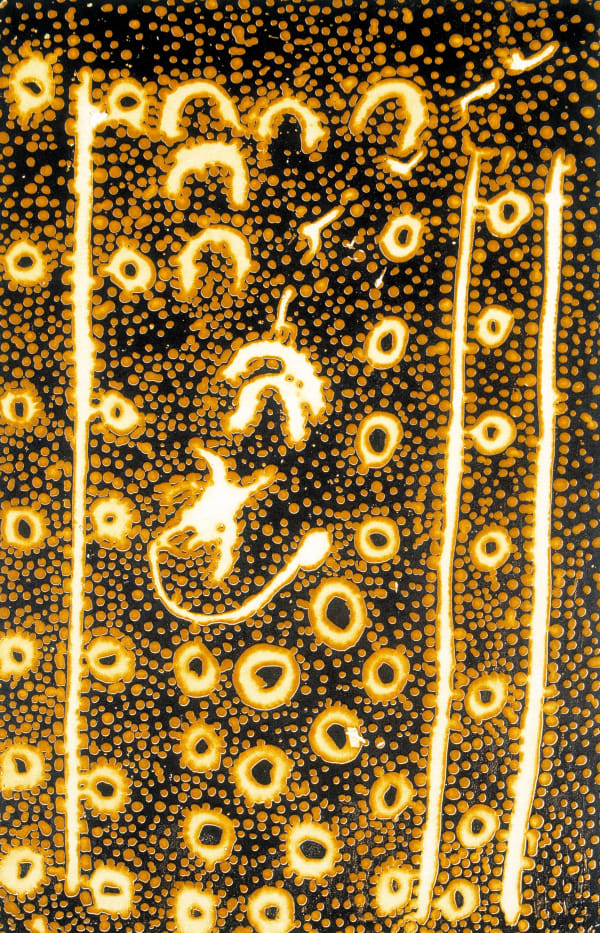

Abie Jangala, Rainbow Men, 2002

Abie Jangala, Rainbow Men, 2002 -

Tjama (Freda) Napanangka, Wati Kutjarra , n.d.

Tjama (Freda) Napanangka, Wati Kutjarra , n.d. -

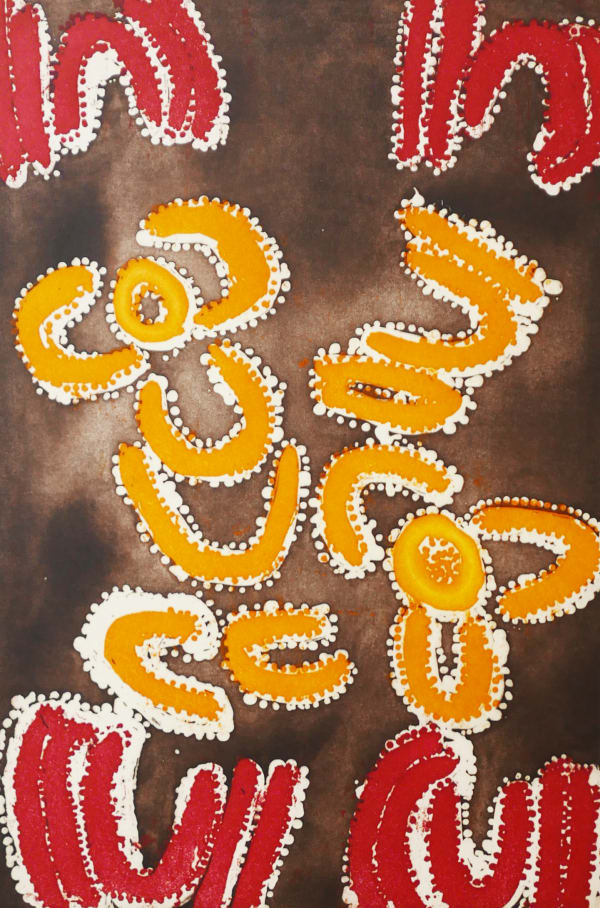

Bai Bai Napangarti, Love Magic Ceremony Design for Ngaanjatjarra, 2002

Bai Bai Napangarti, Love Magic Ceremony Design for Ngaanjatjarra, 2002 -

Eubena Nampitjin, Nakarra Nakarra I, 2002

Eubena Nampitjin, Nakarra Nakarra I, 2002 -

Helicopter Tjungurrayi, This Place my Country, n.d.

Helicopter Tjungurrayi, This Place my Country, n.d. -

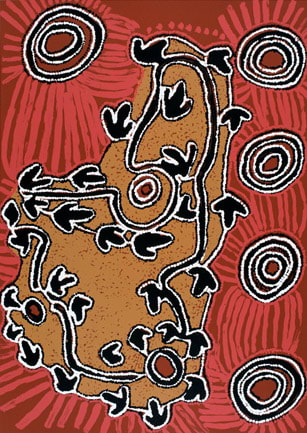

Lily Hargraves, Liwirrinki – Goanna Dreaming, 2002

Lily Hargraves, Liwirrinki – Goanna Dreaming, 2002 -

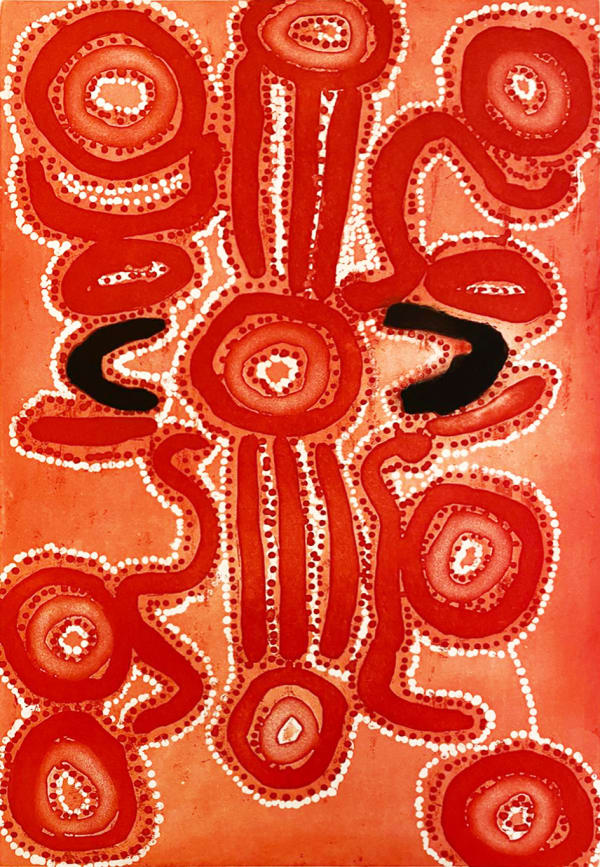

Samson Martin Japaljarri, Ngarlu Jukurrpa – Red Rock Love Story, 2003

Samson Martin Japaljarri, Ngarlu Jukurrpa – Red Rock Love Story, 2003 -

Uni Martin Nampitjinpa, Wayipi Story, 2002

Uni Martin Nampitjinpa, Wayipi Story, 2002 -

Judy Napangardi Martin, Madjardi- Hairstring pubic belt (Women’s love magic) , 2003

Judy Napangardi Martin, Madjardi- Hairstring pubic belt (Women’s love magic) , 2003 -

Elizabeth Nyumi Nungurrayi, Kantil Kantil

Elizabeth Nyumi Nungurrayi, Kantil Kantil -

Ronnie Lawson Tjakamarra, Woman's Dreaming, 2003

Ronnie Lawson Tjakamarra, Woman's Dreaming, 2003 -

Rosie Tasman Napurrula, First Love, 2002

Rosie Tasman Napurrula, First Love, 2002 -

Susie Bootja Bootja, Love Magic, 2002

Susie Bootja Bootja, Love Magic, 2002